Parvati – Goddess of Love & Devotion – Hindu Goddess

The

The

Indian tradition is rich with goddesses. So varied

are her manifestations and names that every village

and every scripture, every art and artist create

their own unique image of her. While sometimes

she is a consort, at other times she is a fertility

goddess; at times she is a benevolent figure yet

at others she is horrific and malevolent. The

tradition is especially replete with a number

of goddesses who are associated with Shiva. But

the one that is artistically and lovingly the

most celebrated is Parvati. Unlike Durga and Kali

who assume their own independent religious status

in the Hindu pantheon and are worshipped and venerated

ritually, Parvati engages the greater attention

of poets and painters, musicians and dancers.

Numerous are her aspects, varied are her persona,

multiple are her attributes and many her names.

Of all the mythic beings in the Hindu pantheon

she is perhaps the most loved and undoubtedly

the most giving of her love. In her we have the

true celebration of Hindu womanhood. Of unsurpassed

sensual beauty, her endowment is not merely physical

but spiritual, not narcissistic but meant as an

offering. In her, it can be said that we have

the grand personification of the Hindu expression,

as well as the concept of beauty.

In classical mythology the raison

d’кtre of Parvati’s birth is to lure Shiva into

marriage and thus into the wider circle of married

life from which he is aloof as a lone ascetic,

living in the wilds of the mountains. The goddess

represents the complementary pole to the ascetic,

world-denying tradition in the Hindu ethos. In

her role as maiden, wife, and later as a mother,

she extends Shiva’s circle of activity into the

realm of the householder, where his stored-up

energy is released in positive ways.

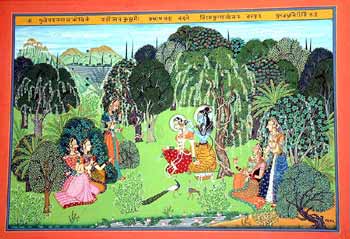

Much as in the Christian art of

Medieval Europe, it is woman the Mother, the Madonna

suckling a babe who has been painted with reverence,

in the Indian Diaspora it is woman the beloved

who has been painted with love and passion. The

female friends of Krishna with their warm sensuous

faces, eyes filled with passion, and delicate

sensitive fingers, represent not the beauty of

a particular woman, but the beauty of entire womanhood.

In fact, she is there as the incarnation of all

the beauty of the world and as a representative

of the charm of her sex.

Parvati’s name, which means “she

who dwells in the mountains” or “she who is of

the mountain, identify her with mountainous regions.

She was the daughter of Himavat (Lord of the mountains)

and his queen Mena. She is usually described as

very beautiful. She showed a keen interest in

Shiva from the outset, repeating his name to herself

and taking delight in hearing about his appearance

and deeds. While she is a child a sage comes to

her house and after examining the marks on her

body predicts that she will marry a naked yogi.

When it becomes clear that she is destined to

marry Shiva, her parents are usually described

as feeling honored. Parvati too is delighted.

At some point during Parvati’s

attempts to attract Shiva’s attention for the

purpose of marriage, the god of love, Kama, is

sent by the gods to awaken Shiva’s lust. When

he attracts Shiva’s attention with sounds and

scents of spring, and tries to perturb Shiva with

his intoxicating weapons, Shiva burns him to ashes

with the fire from his middle eye. But steadfast

in her devotion, Parvati persists in her quest

to win Shiva as her husband by setting out to

perform austerities.

One of the most effective ways

to achieve what a person wants in traditional

Hinduism is to perform tapas, “ascetic austerities.”

If one is persistent and heroic enough, one will

generate so much heat that the gods will be forced

to grant the ascetic his or her wish in order

to save themselves and the world from being scorched.

Parvati’s method of winning Shiva is thus a common

approach to fulfilling one’s desires. It is also

appropriate, however, in terms of demonstrating

to Shiva that she can compete with him in his

own realm, that she has the inner resources, control,

and fortitude to cut herself off from the world

and completely master her physical needs. By performing

tapas, Parvati abandons the world of the householder

and enters the realm of the world renouncer, namely

Shiva’s world. Most versions of the myth describe

her as outdoing all the great sages in her austerities.

She performs all the traditional mortifications,

such as sitting in the midst of four fires in

the middle of summer, remaining exposed to the

elements during the rainy season and during the

winter, living on leaves or air only, standing

on one leg for years, and so on. Eventually she

accumulates so much heat that the gods are made

uncomfortable and persuade Shiva to grant Parvati’s

wish, so that she will cease her efforts.

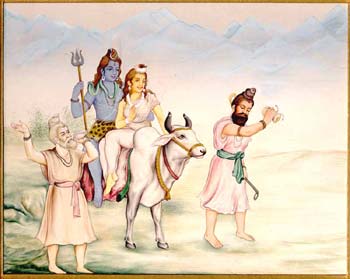

The marriage is duly arranged

and elaborately undertaken. Shiva’s marriage procession,

which includes most of the Hindu pantheon, is

often described at length. A common motif during

the marriage preparations is Mena’s outrage when

she actually sees Shiva for the first time. She

cannot believe that her beautiful daughter is

about to marry such an outrageous-looking character;

in some versions, Mena threatens suicide and faints

when told that the odd-looking figure in the marriage

procession is indeed her future son-in-law.

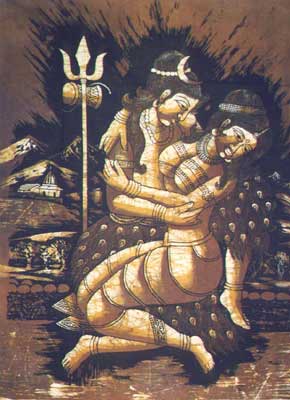

After

After

the two are married they depart to Mount Kailasha,

Shiva’s favorite dwelling place, and immerse themselves

completely in sexual dalliance, which continues

uninterruptedly for long periods of time. The

Love god Kama is resuscitated when Shiva embraces

Parvati and the sweat from her body mingles with

the ashes of the burned god.

Their lovemaking is so intense

that it shakes the cosmos, and the gods become

frightened. They are frightened at the prospect

of what a child will be like from the union of

two such potent deities. They fear the child’s

extraordinary powers. They thus plan to interrupt

Shiva and Parvati’s lovemaking. Vishnu goes with

his entourage of gods to Kailasha and waits patiently

outside the quarters of Shiva. Many years passed

and yet Shiva remained closeted with Parvati.

Vishnu spoke in a shrill and plaintive voice and

entreated Shiva to come out and listen to their

problem. When Shiva disregarded this, Agni (Fire)

disguised himself as a pigeon and entered the

bedchamber of Shiva. Parvati immediately sensed

that her privacy was violated. Shiva withdrew

and a drop of his semen fell on the ground. Agni

in the form of the dove ate the drop of semen.

Parvati however was disturbed and angry that the

gods had assembled and interrupted her erotic

pleasures, and cursed them that all their wives

would be barren. She was particularly enraged

at Agni for having eaten the seed of Shiva.

When Agni was unable to bear the

fiery seed he went to the banks of the Ganga.

At that moment, the wives of the seven sages had

come down to bathe. Six of the wives felt cold

and went towards Agni. Agni dropped the seed and

the seed entered the wives and they became pregnant.

When the sages found this out they admonished

their wives who placed the embryo on one of the

peaks of the Himalayas. Thus was born Kartikeya,

a lustrous child with six heads. Shiva and Parvati

were delighted at the birth of their son and it

added much joy to Parvati who had longed for a

child. We are sometimes told that her breasts

oozed milk in affection when she first saw the

child.

Parvati’s

Parvati’s

maternal instincts were indeed the most powerful

emotions in her life. While Shiva exulted in his

romantic dalliance with her, the true mother in

her longed for a child. She would entreat Shiva

to beget her a son and make her a mother but the

ascetic Shiva would hear nothing of it. She reminded

Shiva that no ancestral rituals are performed

for a man who has no descendants. Shiva assured

her that he had no desire to be a grahastha, householder,

for such a state in life brings fetters. Parvati

was disheartened and seeing her in that state

Shiva pulled a thread out of her red dress and

made a son and gave it to her. Parvati held him

to her breast and he came to life. As he sucked

on her milk he smiled and Parvati, pleased, gave

the son to Shiva. Shiva was surprised that Parvati

had breathed life in a child made of fabric but

warned that the planet Saturn would prove inauspicious

for this child and as he spoke those words, the

child’s head fell to the ground. Parvati was overcome

with grief. Shiva tried unsuccessfully to put

the head back together. A voice in the sky said

that only the head of someone facing north would

stick to this child. Shiva deputed Nandi to find

such a person. Nandi soon found Indra’s elephant

Airavat lying with his head facing north and began

to cut it. Indra intervened but Nandi was eventually

successful, although in the struggle one of the

tusks of the elephant was broken. Nandi took the

head to Shiva and thus was born Ganesha. The gods

celebrated the birth and Parvati was pleased.

In a strange myth it is stated

that Parvati had a third child, Andhaka, and an

interesting legend is narrated behind his birth.

In jest Parvati closed Shiva’s eyes with her delicate

hands and at once a darkness engulfed the world.

The hands of the goddess were drenched in Shiva’s

fluid born of passion, and when this was heated

by the heat of Shiva’s third eye it grew into

a horrific child, blind and gruesome. But Parvati,

true to her nature, lovingly cared for this child

as well. But as Andhaka grew, he became a demon

lusting for his own mother, and was eventually

put to death by Shiva.

For the most part Shiva and Parvati’s

married and family life is portrayed as harmonious,

blissful and calm. In iconography the two are

typically shown sitting in happy, intimate embrace.

There were also many moments of philosophical

discourse between the two. While Shiva taught

Parvati the doctrine of Vedanta, Parvati responded

by teaching him the doctrines of Sankhya, for

if Shiva was the perfect teacher, Parvati too,

as a yogini was no less. Parvati was constantly

by Shiva’s side, encouraging, assisting and, participating

in every activity of his.

An important part of Shiva’s daily

routine was the preparation of bhang, his favorite

intoxicant. Parvati would lovingly collect the

best bhang leaves, crush them and then filter

the decoction through a clean muslin cloth. At

other times Parvati would help Shiva make a quilt

that would keep them warm in the cold nights at

Kailasha. At yet other times she would sit by

his feet massaging them while Shiva reclined under

a tree. Parvati’s greatest pleasure was to serve

Shiva and cater to his every need. Nothing was

more important to her than being useful to her

lord, tending to his every comfort and ensuring

that he would not lapse into his solitary, self-denying

ascetic ways. In these activities she combined

the roles of a caring wife and an affectionate

mother.

But Shiva and Parvati do argue

and insult each other from time to time. Bengali

accounts of Shiva and Parvati often describe Shiva

as an irresponsible, hemp-smoking husband who

cannot look after himself. Parvati is portrayed

as the long-suffering wife who often complains

from time to time to her mother but who always

remains steadfast to her husband.

But

But

Shiva too was passionate in his love for Parvati.

Of the many games they played the one of great

significance was the game of dice. Once it so

happened that Parvati was initially losing to

Shiva, but then gradually the tables turned and

Shiva lost everything he had staked in the game,

including the crescent moon, his necklace and

earrings. When Parvati demanded that Shiva give

everything he had staked, there was a fight between

the two, much to the anguish of their attendants.

Parvati removed Shiva’s snake, the crescent moon

and even his loincloth. The onlookers were put

to shame and Shiva too was enraged and opened

his third eye. Following this incident, the two

separated. Shiva retreated into the wilderness

and Parvati into her quarters. But she was tormented

by this separation and at the bidding of her companions

went in search of Shiva. She took the form of

a shabari, a tribal woman, and approached Shiva

who was deep in meditation. Shiva was attracted

towards the shabari but when he realized that

she was none other than Parvati, he realized his

mistake and united with her much to their joy.

On another occasion, Parvati feels

pique when Shiva calls her by the nickname Kali

(blackie), which Parvati takes as a slur on her

appearance. She resolves to rid herself of her

dark complexion and does so by performing austerities.

Having assumed a golden complexion, she then becomes

known by the name Gauri (the bright or golden

one). In some versions of the myth, her discarded,

dark complexion or sheath gives birth to or becomes

a warrior goddess who undertakes heroic feats

or combat against demons.

The presence of an alter ego or

a dark, violent side to Parvati is suggested in

several myths in which demons threaten the cosmos

and Parvati is asked to help the gods by defeating

the demon in question. Typically, when Parvati

grows angry at the prospect of war, a violent

goddess is born from her wrath and proceeds to

fight on Parvati’s behalf. This deity is often

identified as the bloodthirsty goddess Kali. For

the most part, however, the myths emphasize Parvati’s

milder side. So out of character is Parvati on

the battlefield that another goddess, it seems,

must be summoned to embody her wrath and dissociate

this fury from Parvati himself.

The

The

main theme of the Parvati cycle of myths is clear.

The association between Parvati and Shiva represents

the perennial tension in Hinduism between the

ascetic ideal and householder ideal. Parvati,

for the most part, represents the householder.

Her mission is to lure Shiva into the world of

marriage, sex, and children, to tempt him away

from asceticism, yoga, and otherwordly preoccupations.

In this role Parvati is cast as a figure who upholds

the order of dharma, who enhances life in the

world, who represents the beauty and attraction

of worldly, sexual life, who cherishes the house

and society rather than the forest, the mountains,

or the ascetic life. Parvati civilizes Shiva with

her presence; indeed, she domesticates him. Of

her role in relation to Shiva in the hymns of

Manikkavacakar, a ninth-century poet-saint from

South India, it has been said: “Shiva, the great

unpredictable ‘madman’, is rendered momentarily

sane (i.e. behaves in a socially acceptable manner)

when in the company of the goddess. . . Contact

with his properly cultured spouse seems to connect

him with ordinary social reality and temporarily

domesticates him.”

Throughout Hindu mythology it

is well known that one of Shiva’s principal functions

is the destruction of cosmos. In fact, Shiva has

about him a wild, unpredictable, destructive aspect

that is often mentioned. As the great cosmic dancer,

he periodically performs the tandava, an especially

violent dance. Wielding a broken battle-ax, he

dances so wildly that the cosmos is destroyed

completely. In descriptions of this dance, Shiva’s

whirling arms and flying locks are said to crash

into the heavenly bodies, knocking them off course

or destroying them utterly. The mountains shake

and the oceans heave as the world is destroyed

by his violent dancing. Parvati, in contrast,

is portrayed as a patient builder, one who follows

Shiva about, trying to soften the violent effects

of her husband. She is a great force for preservation

and reconstruction in the world and as such offsets

the violence of Shiva. A seventeenth century Tamil

work pictures Parvati as a patient child who creates

the worlds in the form of little houses. Shiva

is pictured as constantly frustrating her purpose

by destroying what she has so carefully built.

The

The

crazy old madman stands in front,

Dancing, destroying the beautiful little house

that You have built in play.

You don’t become angry, but every time (he destroys

It)

you build it again.

When Shiva does his violent tandava

dance, Parvati is described as calming him with

soft glances, or she is said to complement his

violence with a slow, creative step of her own.

Parvati’s goal in her relationship

with Shiva is nothing less than the domestication

of the lone, ascetic god whose behavior borders

on madness. Shiva is indifferent to social propriety,

does not care about offspring, declares woman

to be a hindrance to the spiritual life, and is

disdainful of the trappings of the householder’s

life. Parvati tries to involve him in the worldly

life of the householder by arguing that he should

observe conventions if he loves her and wants

her. She persuades him, for example, to marry

her according to the proper rituals, to observe

custom, instead of simply running off with her.

She is less successful, however, in getting him

to change his attire and ascetic habits. She often

complains of his nakedness and finds his ornaments

disgraceful. Usually prompted by her mother, Parvati

sometimes complains that she does not have a proper

house to live in. Shiva, as is well known, does

not have a house but prefers to live in caves,

on mountains, or in forests or to wander the world

as a homeless beggar. Many myths delight in Shiva’s

response to Parvati’s domestic pleas for a house.

When she complains that the rains will soon come

and that she has no house to protect her, Shiva

simply takes her to the high mountain peaks above

the clouds where it does not rain. Elsewhere,

he describes his “house” as the universe and argues

that an ascetic understands the whole world to

be his dwelling place. These philosophic arguments

never satisfy Parvati, but she rarely, if ever,

wins this argument and gains a house.

Shiva

Shiva

is a god of excesses, both ascetic and sexual,

and Parvati plays the role of modifier. As a representative

of the householder ideal, she represents the ideal

of controlled sex, namely, married sex, which

is opposed to both asceticism and eroticism.

The theme of conflict, tension,

or opposition between the way of the ascetic and

the way of the householder in the mythology of

Parvati and Shiva yields to a vision of reconciliation,

interdependence, and symbiotic harmony in a series

of images that combine the two deities. Three

such images or themes are central to the mythology,

iconography, and philosophy of Parvati:

- The theme of Shiva-Shakti

- The image of Shiva as Ardhanareshwara

(the Lord who is half woman) - The image of the linga and

yoni

Shiva Shakti

The idea that the great male gods

all possess an inherent power through which they

undertake creative activity is assumed in Hindu

philosophical thought. When this power, or Shakti,

is personified, it is always in the form of a

goddess. Parvati, quite naturally, assumes the

identity of Shiva’s Shakti. She is the force underlying

and impelling creation. In this active, creative

role she is identified with prakriti (nature),

whereas Shiva is identified with purusha (pure

spirit). As prakriti, Parvati represents the inherent

tendency of nature to express itself in concrete

forms and individual beings. In this task, however,

it is understood that Parvati must be set in motion

by Shiva himself. She is not seen as antagonistic

to him. Her role as his Shakti is always interpreted

as positive. Through Parvati, Shiva (the Absolute)

is able to express himself in the creation. Without

her he would remain inert, aloof, inactive. It

is only in association with her that Shiva is

able to realize or manifest his full potential.

Parvati as Shakti not only complements Shiva,

she completes him.

A variety of images and metaphors

are used to express this harmonious interdependence.

Shiva is said to be the male principle throughout

creation, Parvati the female principle; Shiva

is the sky, Parvati the earth; Shiva is subject,

Parvati object; Shiva is the ocean, Parvati the

seashore; Shiva is the sun, Parvati its light;

Parvati is all tastes and smells, Shiva the enjoyer

of all tastes and smells; Parvati is the embodiment

of all individual souls, Shiva the soul itself;

Parvati assumes every form that is worthy to be

thought of, Shiva thinks of all such forms; Shiva

is day, Parvati is night; Parvati is creation,

Shiva the creator; Parvati is speech, Shiva meaning;

and so on. In short, the two are actually one-different

aspects of ultimate reality-and as such are complementary,

and not antagonistic.

Ardhanareshwara

The meaning of Ardhanareshwara

form of Shiva is similar. The image shows a half-male,

half-female figure. The right side is Shiva and

is adorned with his ornaments; the left side is

Parvati and adorned with her ornaments.

In

In

the text of Shiva-Purana it is mentioned that

the god Brahma is unable to continue his task

of creation because the creatures that he has

produced do not multiply. He propitiates Shiva

and requests him to come to his aid. Shiva then

appears in his half-male, half-female form. The

hermaphrodite form splits into Shiva and Parvati,

and Parvati, at Brahma’s request, pervades the

creation with her female nature, which duly awakens

the male aspect of creation into fertile activity.

Without its female half, or female

nature, the godhead as Shiva is incomplete and

is unable to proceed with creation. To an even

greater extent than the Shiva-shakti idea, the

androgynous image of Shiva and Parvati emphasizes

that the two deities are absolutely necessary

to each other, and only in union can they satisfy

each other and fulfill themselves. In this form

the godhead transcends sexual particularity. God

is both male and female, both father and mother,

both aloof and active, both fearsome and gentle,

both destructive and constructive, and so on.

Linga

Linga

and Yoni

The image of the linga in the

yoni, which is the most common image of the deity

in Shiva temples, similarly teaches the lesson

that the tension between Shiva and Parvati is

ultimately resolved in interdependence. Parvati

as a sexual entity succeeds in tempering both

Shiva’s excessive detachment from the world and

his excessive sexual vigor. In the form of the

yoni in particular, Parvati fulfills and completes

Shiva’s creative tendencies. As the great yogi

who accumulates immense sexual potency, he is

symbolized by the linga. This great potency is

creatively released in sexual or marital contact

with Parvati. The ubiquitous image of the linga

in the yoni symbolizes the creative release in

the ultimate erotic act of power stored through

asceticism. The erotic act is thus enhanced, made

more potent, fecund, and creative, by the stored

up power of Shiva’s asceticism.

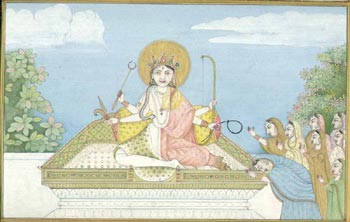

Though most arts give Parvati

a religious aura, including a certain poetic truth,

there is also an expression of both the romantic

and motherly love of Parvati. Possessing a measured

grace and refinement about them, these representations

have a certain earthy charm and spontaneity. In

her this form, Parvati is not only more endearing

and accessible, but also belongs to the shrine

or the walls of the home. These are not mere icons

or visual poetry, but mythic beings reduced to

everyday reality. This real Parvati is the one

that the common man can relate to, worship and

celebrate, in his or her own personal way.

References and Further

Reading

- Dehejia, Harsha. Parvati Goddess of Love: Ahmedabad, 1999.

- Dehejia, Harsha. Parvatidarpana: Delhi, 1997.

- Dehejia, Vidya (ed.). Devi The Great Goddess: Ahmedabad.

- Dhal, Upendra Nath. Goddess Laksmi: Origin and Development: Delhi.

- Gandhi, Maneka. On the Mythology of Indian Plants: New Delhi.

- Gupta, Shakti M. Plant Myths and Traditions in India: New Delhi.

- Kinsley, David. Hindu Goddesses (Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition): Delhi, 1998.

- Pande, Mrinal. Devi (Tales of the Goddess in Our Time): New Delhi.

Add a review

Your email address will not be published *

Please, share this post on Twitter !